Parashat

Bamidbar

How Does

the Wilderness Prepare Us to Inherit the Land of Israel?

What

made Me Embrace the Torah in The Old City of Jerusalem on Shavuot?

This

Shavuot, I celebrate 45 years of Torah! I can hardly believe how the years have

flowed by, like foamy waves softening and refining our hearts, as hardships

etched their traces into the furrows of our faces. I look back with nostalgia

to that first Shavuot – the beginning of my teshuva – when everything was new.

I found myself among a circle of women, sitting on cool stones under the starry

sky in the Old City of Jerusalem. It was the first time I learned about Ruth –

who left behind the comfort of her regal home, her country, and all that was

familiar, to follow her aged mother-in-law Naomi toward an unknown destiny.

I, too,

had recently left my own country, my childhood home, and the prospect of a

prestigious university degree to follow my heart and fulfill an undefined

calling. Was Ruth also a truth seeker, who found the pomp of prosperity

superficial while looking for a deeper meaning and mission in life? I pondered.

Since my

teenage years, I had been searching for truth. I had rejected the Marxism I was

taught in high school, which focused solely on dismantling economic classes without

addressing the values that would define the envisioned society of financial

equality. Dancing in the inner city with born-again Xtians whose theology

conflicted with everything I would later come to value felt exciting at the

time, but their answers rang hollow and rehearsed. Though I was a flower-power

girl immersed in the hippy counterculture, I was never drawn enough to the East

to join my friends traveling to India and Nepal in search of spirituality and

inner vision. Yoga helped me strengthen my body, but it in no way touched my

soul.

I had

never considered seeking truth within my own Jewish heritage. The Jewish

experiences of my youth had led me to believe Judaism was nothing more than a

culinary creed wrapped in outdated rules, lacking any spiritual essence.

Yet here

I was, in the holy city of Jerusalem, at the Women’s Division of the Diaspora

Yeshiva – where I had surprisingly found my spiritual home. I still remember

hearing Rabbi Goldstein proclaim: “Now that you’ve received the Torah, can you

give it back? No, you can’t. You have to keep it!” At that moment, I knew I was

hooked for life.

What

Does it Take to Make our Torah Transformative and Enduring?

The Imrei

Emet explains that the Torah was given to rectify the three core flaws of

humanity – jealousy, lust, and pride – reflected in the sins of early

generations: Kayin, the generation of the Flood, and the Tower of Babel. The

mitzvot at Matan Torah correspond to these: the boundary around Mount Sinai

addressed jealousy – giving each person their designated space; the command to

abstain from marital intimacy represented restraint – countering lust; and

standing humbly at the foot of the mountain symbolized submission – opposing

pride. This is why the Torah was given with fire, water, and wilderness –

representing passion, humility, and self-nullification. Every day, we are

challenged by jealousy, lust, and pride – and only through the power of Torah

can we overcome them. Moreover, to truly acquire Torah, we must make ourselves

like a wilderness – open, humble, and ownerless (Imrei Emet, Bamidbar, 5667).

This concept hits home when I reminisce about those early days of embracing

Torah, most of the students in Diaspora Yeshiva from affluent American families,

made great sacrifices to leave flourishing careers and promising prosperous

futures behind, to dedicate ourselves to Torah learning in the Land of Israel. As

the Imrei Emet teaches, as long as we make ourselves like a desert completely

given over and devoted to Torah and Mitzvot (mesirut nefesh), through

this inner work of surrendering our selves, our Torah becomes transformative

and enduring. Now, 45 years later this concept has proven true through the

descendants of the students of the ‘hippy yeshiva’ raising families deeply

rooted in Torah and mitzvot.

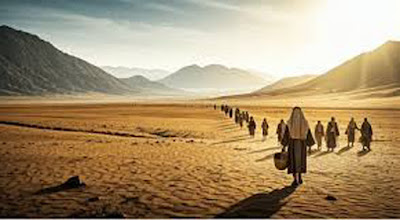

Thus, the desert became a place of alignment – each soul drawn to its specific inheritance, in sync with its Divine source. This is hinted in the verse: וְאִישׁ עַל־דִּגְלוֹ בְאֹתֹת לְבֵית אֲבֹתָם יַחֲנוּ “Each man by his banner, according to the signs of their father’s house shall they camp” (Bamidbar 2:2). The אֹתֹת/otot – “signs” – may be understood as spiritual markers, revealing each tribe’s unique role within the collective mission of Am Yisrael in Eretz Yisrael.

May we each walk our personal midbar with courage and faith – shedding old identities, listening to the voice of Hashem, and preparing our hearts to receive our portion in the Holy Land. And may we soon see the full inheritance of Am Yisrael revealed – each tribe, each soul, restored to its rightful place in the Land.